Antibiogram – microorganisms susceptibility testing

I really like the idea behind this chapter. Educating my readers about topics of this sort was my precise goal when I started this website.

On the one hand, you could look at this topic as a mandatory one that everyone should be familiar with. Antibiogram is actually a test that is carried out on bacterial cultures (the most common one being urine cultures). On the other hand, this is quite an advanced topic, and it is intended for parents who really want to go that extra mile to learn about more advanced topics in the field.

If you stay with me and maintain your focus, you will certainly gain substantial medical knowledge. I don’t think this topic is too difficult to understand.

From here onwards, for the purpose of this post, I will be discussing antibiogram related to urine cultures. However, bear in mind that the concept behind antibiograms and the explanations below are applicable to the cultures carried out on any bodily fluid, be it a blood culture, a stool culture or anything else.

Stay with me, you’re going to love this!

Why do we need to test bacterial cultures in the first place?

Have you heard of a urine test before? Of-course you have! Okay, so here we go.

Usually, urine tests are comprised of two separate tests – the first is a urinalysis, and its purpose is to provide us with a quick answer regarding the presence of white blood cells (leukocytes), red blood cells, ketones, bilirubin, etc. With the help of this test, we can quickly determine whether there is a concern for a urinary tract infection.

Most of you know, however, from your own personal experience that urine samples are also sent for an additional test, called a urine culture, and it usually takes about 48 hours before you get a result for that one.

The purpose of a culture is to try and grow the bacteria that is present in the urine sample under laboratory conditions, in order to learn 2 more important pieces of information:

1. The name of the bacteria that was isolated.

2. The susceptibility of that bacteria to a variety of antibiotics (or in other words, antibiogram testing).

Why is the name of the bacteria found in the culture important?

There are a few reasons for why the name of the bacteria is important.

As I said we’re going to take urine cultures as an example to explain this topic.

If the bacteria isolated in the urine culture is called Escherichia Coli, then it would make sense to me as this is the most common bacteria causing urinary tract infections. If, on the other hand, a bacteria called Proteus is found, it raises a concern for a congenital anomaly in the person’s urinary tract, as this bacterium is less commonly found in the normal urinary tract.

And I could write about so many more examples like the one above.

But there is more to it. The name of the bacteria can help the physician determine what antibiotic to prescribe their patient.

If Escherichia Coli is isolated, for example, we know that it is typically resistant to penicillin and sensitive to the cephalosporin family of antibiotics.

By contrast, if Enterococcus is isolated, then it will always be resistant to cephalosporins and sensitive to penicillin.

In short, the name of the bacteria is vital. But I haven’t reached my point yet about antibiograms.

What happens if more than one bacterium is isolated in a single culture?

Having more than one bacterium grow in a single culture is not very likely, and it usually indicates a contaminated sample of urine. This means that the origin of the microorganisms in the sample is most probably external. The samples of fluids that are cultured are supposed to be sterile fluids, and if they carry an infection then it is usually caused by a single pathogen.

Of course, there are sometimes exceptions to the norm and each case should be studied individually.

What is an antibiogram?

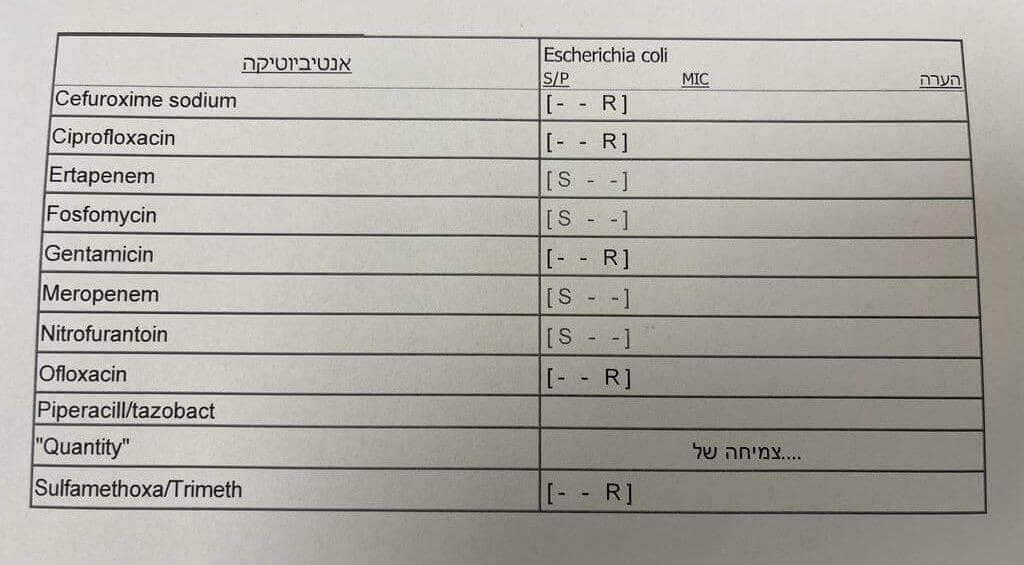

Once a pathogen has been isolated in a culture, a list of antibiotics will follow the name of the pathogen and each antibiotic will have one of the following letters assigned to it:

R – represents resistance, which means the bacteria isolated is resistant to that particular antibiotic

I – represents the term ‘intermediate,’ which means the bacteria is partly resistant to the antibiotic. Practically speaking, we avoid treating infections with antibiotics that the bacteria are intermediate to, unless we really have no choice.

S – means sensitive, which means the pathogen is sensitive/susceptible to this antibiotic.

Sadly, we are currently living at a time where the number of R’s we see on this list is getting larger. This just shows how bacteria these days have become more resistant to our antibiotics. Sometimes, at the hospital, I see cultures without a single S… treating these infections can get very complicated.

Are we familiar with the antibiotics found on antibiograms?

The answer to this is both yes and no.

For example, in the antibiogram image attached to this post, one of the antibiotics listed is cefuroxime sodium. Are we familiar with this antibiotic? Yes, we are. It is sold under many brand names such as Ceftin, Cefuroxime Axetil, Kefurex, Zinacef and more (you can read more about it here).

Remember, the antibiogram will list the generic names of the antibiotics, not the trade numbers.

Do antibiograms list every single antibiotic out there?

No. Specific antibiotics will be listed depending on the fluid being cultured and the bacteria isolated.

Are antibiogram available for all cultures tested?

No. A classic example of cultures that are frequently tested but does not come back with an antibiogram result are throat cultures for Streptococcus. The results for this culture only indicate whether or not Group A Streptococcus is present. Susceptibility testing will not be available for this culture.

And why is that? This is because the Group A Streptococcus bacterium is always sensitive to penicillin, and that is the treatment of choice for this infection. There is no need to perform susceptibility/resistant testing for other antibiotics for this bacteria.

But I’m sure you were already familiar with this information, as you must have already read this post on my website.

Are antibiograms available only for bacterial cultures?

No. Susceptibility testing is also carried out on fungal cultures to test for sensitivity for antifungals, but not so much for viral pathogens.

How is the susceptibility of a certain bacteria to an antibiotic determined?

Very good question.

There is an organization called The Clinical & Laboratory Standards Institute (or in short CLSI), that determines the threshold levels for susceptibility or resistant of certain antibiotics to bacteria.

With the help of different laboratory methods, labs carry out tests to determine whether the specific bacteria surpass the threshold cut-offs set by the CLSI and they then report the susceptibility of the bacteria in the form of an antibiogram.

Should I, as a parent, learn how to read an antibiogram in such a way so I can decide what antibiotic I should treat my child with?

The answer to this is again both yes and no.

There is no doubt that the purpose of this post is to give you the tools to comprehend what an antibiogram presents. Maybe, one of these days, you will even happen to find out that your child is being treated with an antibiotic that is not suitable for the bacteria that was found in their culture, and you could be the one to point it out to your doctor (if he happens not to notice it before you do).

On the other hand, when I wrote this post, I had no intention of turning you into microbiologists nor did I expect you to become professionals at choosing the correct antibiotic for your child all alone because it can get a lot more complicated than the simplified information on this website.

Here’s an example:

The bacteria Enterococcus is one of the bacteria that can cause urinary tract infections. If you take a look at the antibiogram of this bacterium, you will notice that it indicated that Enterococcus is sensitive to the antibiotic gentamycin. But this is not true in reality…

The only time Enterococcus is sensitive to gentamycin is when gentamycin is combined with another drug. Therefore, if you were to treat an Enterococcus infection with gentamycin alone, it just wouldn’t work, and the bacteria would not get destroyed

In other words, it can get really complicated.

I certainly do advise you to take a look at the antibiogram, and make sure that your child is receiving the antibiotic that the isolated bacteria is susceptible to.

In summary, ever since I started this website, my goal has been to turn my readers into knowledgeable individuals, so that they are aware and understanding of information that would have otherwise been restricted to medical practitioners.

For those of you who have made it this far, I truly believe this post meets that goal.

For comments and questions, please register