Everything you need to know about scoliosis and kyphosis – from diagnosis to treatment

This is an important topic that is often overlooked by primary care physicians, either due to a lack of awareness or a lack of knowledge about the various tests that can aid in diagnosis. As a result, many cases are discovered incidentally—sometimes by the parents themselves—and often when it is too late.

As I have already mentioned, this chapter is of great importance because early diagnosis and prevention of spinal deformities can be very helpful. I suggest that anyone who is a parent of an adolescent read this chapter and possibly even try some of the tests I will discuss on yourself.

What are the two types of abnormal spinal curvatures in children?

Often, people will tell you that they’ve noticed your child doesn’t walk “straight.” Their shoulders may be asymmetrical, and their back might appear curved forward. The thought that this could be scoliosis or weakness of the shoulder girdle may come to mind, along with concerns that their back will worsen as they grow older.

First, it’s important to differentiate between two types of situations, depending on how flexible the curvature is: Is your child experiencing a flexible curve—one that can be corrected by asking them to stand up straight—or is it a rigid spinal curve, i.e., one that cannot be corrected during the physical examination?

The second factor to assess is the direction of the curve: Is it a forward bend (kyphosis), or is part of the trunk curved to one side (scoliosis)?

The flexible cases – “My child doesn’t walk straight”

Whether your child bends forward (the more common case of “my child does not walk straight”) or to the side, this is usually due to abnormal postural habits.

This is not true scoliosis but is related to poor posture. The curved stance is often very concerning to parents… while the child usually doesn’t understand what the problem is or why they are being told to stand up straight. Medically, the reason for encouraging upright posture is that consistently walking with a curved spine can lead to muscular back pain from continuous contraction of muscles in that position. Over time, this may even develop into a structural issue, where the child can no longer straighten their back even if they want to.

In cases of flexible side curvatures, one common underlying cause that should be considered is leg-length inequality. When one leg is shorter, the spine may curve toward that side to compensate.

Treatment of flexible spinal curvatures involves two main components: strengthening the core muscles (back and abdomen) and increasing awareness of proper posture. This begins with physiotherapy exercises and continues with regular home practice. Daily exercise is a good way to enhance body awareness. Simply strengthening core and shoulder-girdle muscles does not guarantee future postural correction—consistent practice is essential.

A common question parents ask is whether a brace is needed to help maintain proper posture. We strongly advise against using a brace for this purpose. Rather than helping, the passive support from a brace can weaken the back muscles and lead to dependence on the device. Posture may actually worsen once its use is discontinued.

Side curvatures caused by leg-length inequality are managed by elevating the shorter leg with an orthotic device to stabilize the pelvis and correct the asymmetry. Leg length should be monitored regularly in such cases, and treatment should be adjusted accordingly. If the difference exceeds 2 centimeters, surgical intervention may be considered.

Rigid situations – these are structural spinal curvatures such as scoliosis and kyphosis

Scoliosis (curvature to the side)

This is the most common spinal curvature, and I will dedicate most of this chapter to it. It mainly develops during adolescence, and the severe form is seven times more likely to occur in girls than in boys. The most frequent structural curvature is called “idiopathic scoliosis” (idiopathic meaning “of unknown cause”) and accounts for 80% of structural curvatures. It is not a congenital abnormality, but one that arises during development and growth after age 10. It may be mild and hidden in its early stages but tends to become more severe and noticeable during adolescence.

The cause of scoliosis remains unknown. However, there is a strong genetic component, and a positive family history can help with risk assessment and the prediction of severity. The worsening of scoliosis is due to changes in the shape of the vertebrae themselves, which become more apparent as the child grows. The most common type of structural curvature appears in the thoracic spine (the upper portion of the vertebral column made up of 12 vertebrae, as opposed to the lower lumbar spine, which consists of 5 vertebrae). In scoliosis, the spine typically curves to the right, meaning the curve’s apex points rightward.

The shape of a scoliotic curve involves not only lateral bending of the vertebrae but also a significant rotational component, where the vertebrae themselves rotate along the horizontal axis.

This same deviation is what causes the curvature of the chest cavity that is easily visible during a physical examination: when bending forward, one can observe asymmetry at the level of the rib cage on both sides of the spine—viewed from the back (Adams forward-bending test; see the image and explanation below).

Often, the side curvature appears before the lateral deviation, which is why screening and early diagnostic tests focus on identifying the side curvature first. Another component of scoliosis is an exaggerated straightening of the vertebral column in the front-to-back (sagittal) plane.

What are the findings in scoliosis? How can it be identified?

There are several findings on physical examination that support the presence of scoliosis. These include:

– Asymmetry of shoulder height

– Asymmetric scapular or shoulder position

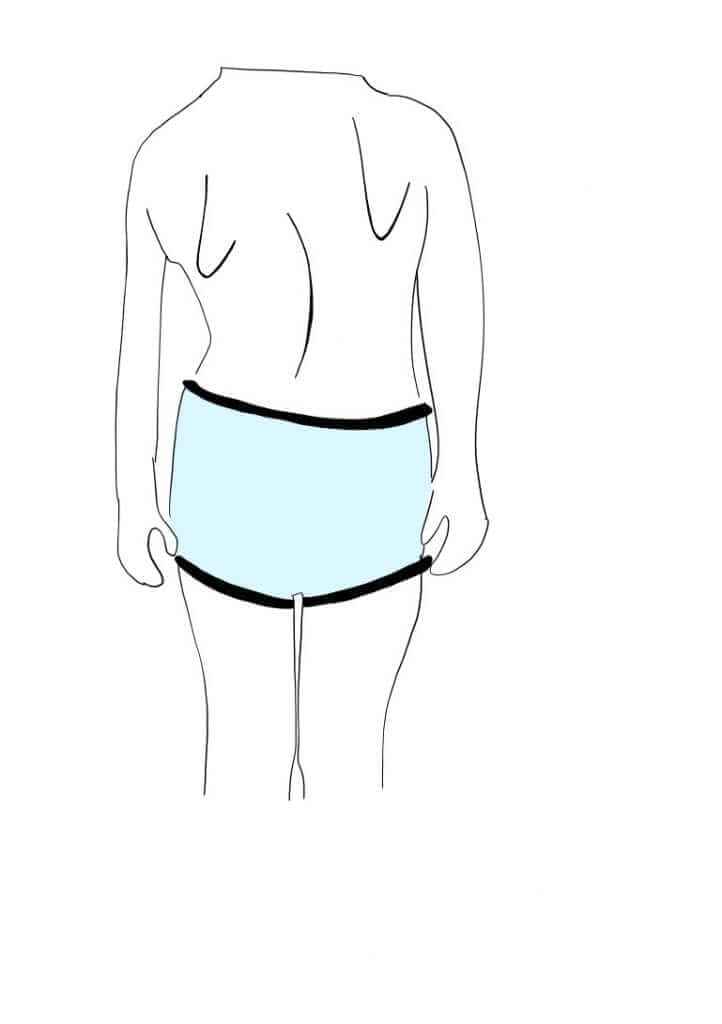

– Asymmetry in the distance between the hands and the body

– Pelvic orientation toward one side of the body

What is Adams forward-bending test?

Adams forward-bending test – this used to be a simple screening test performed by school nurses, but all parents can perform it at home.

How is it done? The parent sits behind their child, with their eyes level with the child’s back while it is bent forward. The child is asked to bend forward with legs tightly together and knees straight, creating a right angle at the hips. If there is a curvature, a protrusion or asymmetry will be visible along the spine.

As previously mentioned, this is a structural, developmental problem. As the child grows, there is a risk that the curvature will worsen, typically until the child finishes growing. Once growth has stopped, the progression also stops and the deviation stabilizes.

The challenge in treating the curvature is that once it appears, there is no conservative (non-surgical) way to reverse the structural changes that have already occurred. Various conservative methods have been tried throughout history, but unfortunately, they have not proven effective in correcting structural curves. It is true that in most cases, especially in early stages, there is a secondary flexible component to the rigid curvature, and strengthening this flexible part can slightly improve posture. However, this does not prevent scoliosis from progressing, nor does it correct the curve.

The traditional method of bracing remains the only conservative technique proven to help, preventing curve progression in about 80% of cases.

Bracing involves wearing a type of ‘belt’ that encases the upper body, made from rigid plastic and custom-designed for the patient.

There are several types of braces created by orthotists in orthopedic centers that specialize in spinal deformities. The orthotist’s skill in preparing the brace is crucial. The brace should be worn most of the day—about 22 hours daily—meaning it should only be removed briefly for activities like bathing and physical exercise. Therefore, choosing bracing as a treatment is a difficult decision, and it’s important to understand how and when it should be used.

A scientific article was recently published that, in our opinion, emphasized the need to wear the brace for most hours of the day. If you’d like to learn more about this, follow the link here.

The degree of spinal deviation is measured using an X-ray taken while the patient is standing, showing the entire spine and pelvis. The angle is measured from the first curved vertebra to the last. The decision to use a brace depends on the degree of curvature and its potential for progression. Any curve greater than 20 degrees should be treated with a brace—as long as the child is still growing. The potential for progression depends on the patient’s age, developmental stage, and bone age. The younger the patient, the higher the likelihood of curve progression. For example, a 16-year-old with a 30-degree curve is usually not a candidate for bracing, as growth has likely ended, and the risk of worsening is minimal. Because this decision can be complex, some experts recommend monitoring the curve and beginning bracing only if progression is observed.

Surgical treatment for idiopathic scoliosis is reserved for the most severe cases—typically curves over 45 degrees, or curves that continue to progress despite conservative management. Surgery is recommended for curves over 50 degrees, as they may continue to worsen even after growth has stopped. While post-growth progression is slow (around one degree per year), it can lead to significant deformity and even respiratory issues over time.

Some important points to mention:

Remember, in most cases scoliosis is primarily a cosmetic issue. Medical concerns arise when curves exceed 70 degrees or when atypical curvatures appear in early childhood (before age 10).

In the majority of cases, scoliosis does not lead to long-term physical limitations, and patients usually have no issues with physical activity, pregnancy, or other aspects of life.

There is some evidence suggesting that adults with idiopathic scoliosis may experience increased back pain over time, but the evidence is inconclusive. One challenge with idiopathic scoliosis is that it typically does not cause pain early on, which often delays diagnosis. The main issue is emotional, related to self-image and confidence.

It’s important to understand that delaying treatment can lead to worsening of the curvature. If treatment is indicated, it should begin as early as possible to prevent irreversible damage during growth spurts.

Another important point involves how scoliosis is measured and monitored.

There is no better tool than an X-ray for assessing spinal curvature. The degree of scoliosis cannot be reliably measured using ultrasound, MRI, or other imaging methods.

Concerns about radiation exposure from repeated X-rays are valid. However, most centers that manage spinal deformities use X-ray machines with reduced radiation, specifically designed for imaging the spine. It is reasonable to request that such machines be used for follow-up imaging.

Kyphosis (deviation with a forward curve)

Kyphosis is less common than scoliosis.

It is caused by wedge-shaped vertebrae, where the front part of the vertebral body is angled, leading to a forward curve of the spine. Kyphosis affects males and females equally.

On physical examination, there is a visible forward curve in the spine, noticeable from the side. Structural kyphosis, unlike postural kyphosis, does not improve when the person attempts to stand up straight or bend backward.

Similar to scoliosis, structural kyphosis is treated mainly with a combination of exercises to strengthen the spinal postural muscles and braces that support the spine and guide its growth in a straighter direction.

What is the main take-home message for parents?

There are several areas in pediatrics where parents play a critical role in early detection and diagnosis. Spinal curvature is one of them.

I encourage all parents of adolescents to become familiar with the signs mentioned in this chapter and to perform the Adams test on their child if needed.

If you notice anything unusual, consult an orthopedist for a full evaluation.

For comments and questions, please register