Otitis media in children (ear infection) – how is it detected and managed?

Almost everyone has had their ears checked at some point—or been told by their mother that they might have an ear infection. Ear infections are one of the most common reasons children visit the pediatrician, and they are also a leading cause of antibiotic prescriptions.

Unfortunately, this is a condition that is often either misdiagnosed or managed inappropriately. Sometimes it’s missed due to difficulties in properly visualizing the eardrum, and other times it’s over-diagnosed.

When it comes to ear infections, understanding the ear’s anatomy is essential. I believe that parents who can grasp the basic anatomy will gain valuable insight into the different types of ear infections and how they are treated.

Please note: this post focuses specifically on otitis media, which is an infection of the middle ear. It does not cover

ear fluid (otitis media with effusion) or external ear infections (swimmer’s ear).

If you’re interested in learning more about recurrent ear infections and how to manage them, I recommend checking out our dedicated post on that topic.

What is the structure of the ear and what do we mean when we say middle ear?

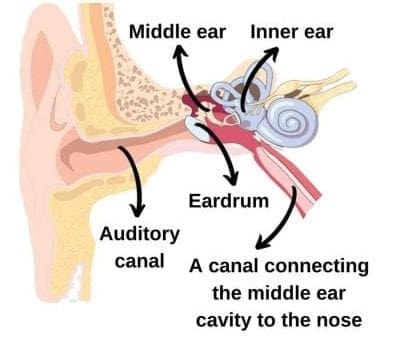

Take a look at the illustration provided here. The ear is composed of three distinct parts: the external ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear.

External Ear

We’re all familiar with the auricle—the outer, cartilaginous part of the ear. At the center of the auricle is an opening that leads into the auditory canal. A few centimeters inward lies the eardrum, which marks the boundary between the external ear and the middle ear.

External ear infections (swimmer’s ear) are discussed in a separate section on this website.

Middle Ear

The middle ear begins at the eardrum, a delicate membrane that vibrates in response to sound waves. These vibrations are transferred to three tiny auditory bones located just behind the eardrum. The last of these bones connects to another small membrane called the oval window, which marks the boundary between the middle ear and the inner ear.

Inner Ear

The inner ear is a closed space that contains key auditory structures, including the cochlea and labyrinth. These organs convert sound vibrations into electrical impulses that are transmitted to the brain, allowing us to hear.

So what is a middle ear infection?

The middle section of the ear—the part that often causes trouble—is where typical ear infections occur.

It’s important to understand that the middle ear is connected to the nose by a canal (the Eustachian tube), which links the middle ear cavity to the back of the nasal passage. This explains why the middle ear loses ventilation when this canal becomes blocked or congested (for example, in a child with a runny nose and enlarged adenoids or a “third tonsil”).

How prevalent is otitis media in children?

Because medical literature includes various conditions under the term “ear infections,” such as ear fluid (effusion), it’s difficult to estimate the exact prevalence. However, otitis media is undoubtedly a common illness in infancy and early childhood, especially in the first two years of life. That said, ear infections can occur at any age.

Several factors influence the likelihood of developing otitis media—some are modifiable, others are not. For example:

Age – Otitis media is most prevalent in children under age 2. After that, rates decrease but remain elevated in early school-aged children.

Gender – Boys tend to experience it more frequently than girls.

Genetics – Some families have a higher predisposition, though the exact genetic mechanism is not fully understood.

Breastfeeding – Breastfeeding has a protective effect, as explained in this link.

Exposure to tobacco – Passive smoking is a significant risk factor.

Exposure to other children – Attendance at daycare increases the risk due to more frequent viral infections.

Seasonality – Since many bacterial ear infections follow viral upper respiratory infections, it’s easy to see why most occur in winter.

Other contributing factors include using pacifiers and feeding with a bottle while the child is lying flat.

What are the most common bacteria that cause ear infections in children, and do we have vaccines for them?

The three most common bacterial causes of ear infections in children are:

Streptococcus pneumoniae – Vaccination (Prevnar 20) is usually given at 2 months, 4 months, and 1 year of age in many countries. Although this vaccine has reduced the number of infections caused by this bacterium, it has not eliminated them completely.

Non-typeable Haemophilus influenzae – There is no vaccine for this strain. (Note: This is not the same as Haemophilus influenzae type b, for which a vaccine does exist.)

Group A Streptococcus – Yes, the same bacteria that causes strep throat. There is currently no vaccine for this organism.

Understanding the bacteria involved helps guide the doctor’s choice of antibiotic treatment, as you’ll read later.

What are the signs and symptoms of ear infections in children?

Symptoms can vary by age. The most common symptom is **ear pain**, which may present as irritability or poor sleep—often worsening at night. Fever may or may not be present.

Keep in mind that ear infections often occur after several days of an upper respiratory tract infection.

**Pulling or tugging at the ear**, by itself, is not necessarily a sign of infection. It can be a sign of fatigue, frustration, or teething in young children.

What is the doctor looking for when examining your child’s ear?

When using an otoscope, the doctor examines the eardrum for several key indicators:

– Turbidity (cloudiness)

– Bulging

– Redness

– Loss of the normal shape or contour of the eardrum

– Absence of the light reflex

The **most significant findings** are bulging and turbidity of the eardrum.

An ear examination is **not painful**, even in the presence of an infection. While the child may find the process unpleasant or stressful, the exam itself does not cause injury or pain.

To clarify: parents sometimes believe their child has an ear infection because the child winces when the outer ear is touched or during a temperature check. This is **not** a reliable sign of otitis media.

The doctor will always examine both ears and typically begin with the ear that is not reported to be painful.

What are the two different approaches to treatment of otitis media, and when will the doctor choose one over the other?

The two primary treatment approaches are:

– **Watchful waiting** – Delaying antibiotic treatment to see if the infection resolves on its own.

– **Immediate antibiotic treatment** – Starting antibiotics right away.

Which approach is chosen depends on factors such as the child’s age, the severity of symptoms, the presence of fever, whether the infection is in one or both ears, and the overall health and risk factors of the child.

What is the watchful waiting approach when it comes to otitis media and when will the doctor offer it?

Based on several studies showing that antibiotics have limited effectiveness in treating otitis media in children, a more conservative approach has been developed. In specific cases, it is safe and appropriate to delay antibiotic treatment.

The advantage of the watchful waiting approach is avoiding unnecessary antibiotic use. Antibiotics not only target the infection-causing bacteria but also affect beneficial bacteria in the body—especially those in the intestines. Additionally, repeated antibiotic use can promote antibiotic resistance.

Watchful waiting is typically offered to parents of children who:

– Are older than 6 months

– Are previously healthy

– Do not show severe eardrum bulging

– Do not have a fever over 39°C

– Are not excessively irritable

– Do not have infections in both ears

The doctor must provide proper follow-up—either in person or by phone—within the first few days of illness to monitor progress and decide whether treatment is needed.

Importantly, parents must agree to this approach.

In practice, the watchful waiting approach includes:

– Pain relief using acetaminophen or ibuprofen

– Anesthetic ear drops for localized pain

– Observation for 24–48 hours

From my experience, this method is very successful when applied to the right children—and the right parents. It tends to fail in younger children with fever and prominent signs of infection during examination.

Also, pain management is essential, as persistent pain is the most common reason parents abandon watchful waiting. In the right candidates, this approach can reduce antibiotic use for ear infections by up to 50%.

What is the immediate treatment approach and when will the doctor offer it?

This approach involves starting oral antibiotics right away. It is recommended in children who do not meet the criteria for watchful waiting.

Immediate treatment is always advised for:

– Children under 6 months of age

– Children with underlying medical conditions

– Children with high fever or significant eardrum findings (bulging, turbidity)

– Children with infections in both ears

Even with immediate antibiotic treatment, it’s important to manage pain aggressively using acetaminophen, ibuprofen, and local anesthetic ear drops.

What is the antibiotic of choice when it comes to treatment of acute otitis media in children?

The first-line treatment for acute otitis media is Amoxicillin, typically prescribed for 7–10 days (14–20 doses).

If a child is allergic or sensitive to Amoxicillin or other penicillins, the alternative is usually a macrolide, most commonly Azithromycin, taken for 3–5 days.

If the infection does not improve—or worsens—despite appropriate treatment with Amoxicillin, the second-line treatment is Amoxicillin-Clavulanic Acid. There are two forms of this medication used in children (400 mg and 600 mg), and you can read more about them here. Your pediatrician will decide which type and dose is most appropriate.

Reassessment at the end of treatment is usually not required unless specifically requested by your pediatrician.

Are ear infections infectious and when can the child return to their daily activities at daycare/school?

Acute bacterial otitis media is not contagious. A child may return to daycare or school 24 hours after the fever subsides and once they are feeling well, even if they are still taking antibiotics.

When should we refer to a pediatric ENT specialist?

A pediatric ENT specialist is helpful in managing more complex cases, especially when:

– There is concern for otitis media but the eardrum cannot be visualized (often due to earwax)

– First-line and second-line treatments have failed

– The child experiences recurrent otitis media

In cases of recurrent infections, further evaluation (e.g., for enlarged adenoids) is often necessary, and a referral to an ENT specialist is strongly recommended.

How should discharge from the ear be managed and why does it happen?

Discharge from the ear during an infection typically results from a tear in the eardrum, allowing mucus to drain into the ear canal and outer ear. You can learn more about this condition in this article.

What are potential harms of ear infections? Can it cause hearing loss?

Untreated ear infections can lead to complications ranging from localized to systemic infections. It’s essential to consult your pediatrician whenever you suspect an ear infection.

In general, **acute otitis media does not cause hearing loss**. In contrast, **otitis media with effusion (fluid in the ears)**—discussed in a different chapter—can affect hearing.

Recurrent infections, especially those that lead to eardrum perforation, may eventually alter the eardrum’s structure and affect hearing. In such cases, a pediatric ENT consultation is advisable.

What needs to be done when there are recurrent ear infections?

Due to the importance and frequency of this issue, I have created a dedicated chapter on managing recurrent ear infections. You can find it in the following link.

In summary, this is one of the most important topics in pediatrics. I hope this chapter helps you and provides the tools you need to better understand and manage acute otitis media in your children.

We’ll now move on to a brief Q&A to make sure you’ve mastered this topic!

Summary of Ear Infections in Children

What is otitis media?

Otitis media is an inflammation or infection of the cavity located behind the eardrum. It can occur at any age but is most common in infants and young children.

What are the signs and symptoms of otitis media?

The main symptoms include ear pain, irritability, and often fever.

When you see a baby tugging at their ear — is it a sign of otitis media?

Usually not. Ear tugging in babies is often a sign of fatigue or frustration and does not necessarily indicate an ear infection.

How are ear infections in children treated?

Treatment depends on the child’s symptoms and the appearance of the eardrum. In some cases, the doctor may recommend a “watchful waiting” approach. In others, they may advise starting antibiotics right away.

Does otitis media cause pain when pressing on the outer ear?

No. Pain when pressing on the outer ear is more typical of an external ear infection (also known as swimmer’s ear). This type of infection requires a different treatment approach.

How are recurrent ear infections in children managed?

Begin by reading this chapter and consulting your primary care physician. Ask: Has your child truly experienced recurrent ear infections? Are there modifiable risk factors? Is there an enlarged third tonsil or fluid in the ears that might require surgical intervention?

For comments and questions, please register