Everything you need to know about laryngomalacia in infants

I am so happy that the time has come for us to cover laryngomalacia on this website. And why is that? Because, although it’s not a very central topic in pediatrics, the fact that it has made it to this website means that our content is expanding — and that makes me very pleased.

Okay, laryngomalacia — like I said, not a very central topic, but still an important one, especially in babies who present with recurrent episodes of stridor.

We already have a chapter about stridor, which was posted a long time ago, and you can find it at this link. This time, we’re going to focus on one of the causes of recurrent episodes.

The following post was written by Dr. Roy Hod, a senior otorhinolaryngologist who is also listed on our website’s recommended physicians page.

What is laryngomalacia?

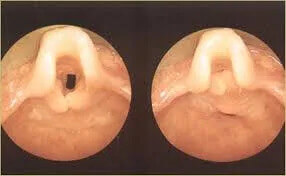

Just after the mouth and before reaching the windpipe, there is a region referred to as the larynx. This structure is made up of cartilage and muscles—see the image attached.

At a very young age, as you will learn below, the cartilage is soft and the muscles are weak, which can cause them to collapse during inspiration (when air is coming in). In the image, you can see an open larynx and one that has collapsed following inspiration. The sound you hear is called stridor.

Who are the babies that suffer from laryngomalacia?

It occurs in young babies, starting in their second week of life, and typically lasts until around 1.5–2 years of age. There is usually gradual improvement over time.

What is special about stridor that occurs in children with laryngomalacia?

In most cases, stridor simply improves with time. However, specialists know that the sound of stridor can vary depending on the cause. In children with stridor due to laryngomalacia, the sound occurs during inspiration and worsens when the child is crying, irritated, feeding, or lying on their back.

How is the diagnosis of laryngomalacia made?

The symptoms usually raise clinical suspicion, without the need for invasive examinations.

Nonetheless, to confirm the diagnosis, a laryngoscope (camera) is inserted through the nose so that the physician can view the area directly. The procedure is performed at a pediatric ENT doctor’s office and takes about half a minute.

A chest X-ray or X-ray of the windpipe is not usually required.

In severe or persistent cases, a more extensive investigation is required, including examination of the entire respiratory tract with the help of a camera (bronchoscopy).

What other findings can accompany laryngomalacia?

Sometimes, these children may present with feeding difficulties, which are usually mild, causing prolonged feeding times and insufficient weight gain.

That is why children with laryngomalacia must be monitored closely by their pediatricians.

How can laryngomalacia be treated?

Most cases do not require any treatment, and time alone often leads to improvement. As time passes, the respiratory tract grows and strengthens, the stridor improves, and eventually disappears.

To help improve stridor, you can place the baby on their tummy or on their back on a mattress elevated at a 30-degree angle.

In severe cases (e.g., insufficient weight gain, weight loss, or cyanotic episodes where the baby turns blue), surgical intervention may be necessary.

In summary, we have learned about laryngomalacia—a diagnosis that is generally favorable in pediatrics and usually requires explanation, reassurance, and patience until it resolves.

Good luck!

For comments and questions, please register