Otitis media with effusion (ear fluids)

Ear fluid—more accurately referred to as otitis media with effusion—is a very common condition in pediatrics, and it can be quite confusing for parents.

That’s why I believe that a parent who understands the main differences between acute otitis media (see here) and otitis media with effusion (ear fluid) can help their child receive better and more appropriate care from their pediatrician.

I wrote the following chapter with the help of Dr. Roy Hod, an outstanding specialist in otorhinolaryngology, who is also listed among the recommended physicians on Dr. Efi’s website.

What is otitis media with effusion (ear fluid), and how do fluids reach the ear?

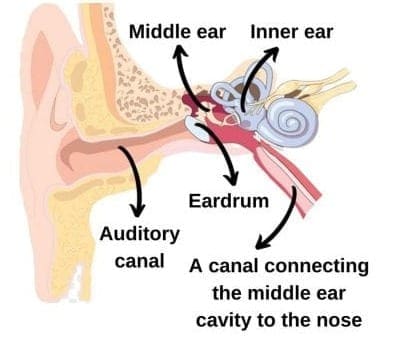

Take a look at the image of the ear structure, which is composed of three parts: the external ear, the middle ear, and the inner ear.

The middle ear is essentially a cavity that begins at the eardrum and ends at a small membrane called the oval window, which marks the start of the inner ear. From this same middle ear cavity, another passage extends, opening into the space behind the nose.

When people hear the term “ear fluid” for the first time, they often imagine water entering through the nose or ear canal. In reality, it is an inflammatory process, where secretory fluids—composed of mucus and inflammatory cells—accumulate in the middle ear.

In children, several risk factors and triggers can cause this fluid buildup, including genetics, passive smoking, and recurrent viral infections.

However, the most significant factor is anatomical structure. If the passage that connects the middle ear to the nose is blocked (due to recurrent viral infections, enlarged adenoids, etc.) or functions poorly (e.g., if it is short, narrow, or angled too horizontally), it affects middle ear ventilation, leading to fluid accumulation.

What is the association between the third tonsil and ear fluid?

The third tonsil (also known as the adenoid or, as some people call it, a polyp) is a tissue located at the back of the nose in children.

It is situated very close to the passage that connects the middle ear to the nose. If the adenoid is enlarged and obstructs drainage or ventilation of this passage, it can lead to otitis media with effusion.

Therefore, as you’ll read below, we often recommend a combination treatment: insertion of ventilation tubes and removal of the adenoids.

If you would like to learn more about the third tonsil in children, follow this link.

What is the association between otitis media with effusion (fluid) and acute otitis media?

On one hand, these are two distinct processes that occur in the same location. On the other hand, they may represent a spectrum of the same disease—where the beginning of one could mark the end of the other. It’s a bit complex.

Ear fluid – a chronic, non-infectious inflammatory process. If we sample this fluid, it will typically be sterile (though this is a simplification). Therefore, treatment with antibiotics is usually ineffective.

Acute otitis media – an acute infectious process, typically caused by bacteria. In this case, antibiotic treatment is appropriate.

In practice, the relationship between the two conditions is more nuanced. Some believe they are points along the same disease continuum. Acute otitis media often begins where otitis media with effusion ends.

To summarize: ear fluid creates an environment that may allow bacteria to grow, although in most cases it causes no harm and does not lead to acute otitis media.

How can we distinguish between otitis media with effusion (fluid) and acute otitis media?

Sometimes, it is difficult to distinguish between the two, and the help of a trained eye may be needed. In both conditions, fluid behind the eardrum and possibly slight bulging can be observed. However, ear fluid (otitis media with effusion) is a chronic condition that does not cause pain, while acute otitis media is typically painful, accompanied by fever, and shows additional findings on the eardrum such as redness, bulging, and turbidity.

Is otitis media with effusion (ear fluid) contagious?

Fluid in the ear is not contagious and should not affect a child’s daily activities, including attending school or daycare.

Can ear fluid cause hearing loss? Which children need to be investigated for hearing loss?

In most cases, ear fluid can cause a mild conductive hearing loss, but it is usually short-lived. This type of hearing loss in children is often insignificant. However, in some cases, it can cause hearing loss of up to 50 decibels, which is considered moderate.

If the loss is only in one ear, the child may not notice it. But if it is in both ears, is of a considerable degree, and is prolonged, it can significantly impact hearing and speech development.

It is especially important to monitor children who already have developmental delays (speech, behavioral, or cognitive), as even a minor reduction in hearing can negatively affect their condition. These children should receive appropriate follow-up and evaluation.

Therefore, in children who seem to have hearing loss that affects their daily functioning, or in those with persistent ear fluid for more than three months, it is important to perform a proper hearing test. An effective hearing test should be performed at a specialized auditory center with experience in evaluating children, and should accurately assess each ear separately, with and without fluid.

Some people tend to associate hearing loss—whether or not caused by ear fluid—with a wide range of challenges, such as behavioral issues or attention deficits. While, hypothetically and according to medical literature, prolonged ear fluid may contribute to such problems (including posture disturbances), it is important to remember that in most cases, ear fluid comes and goes over several months and does not cause significant issues in children.

What are the available treatments for ear fluid in children?

Once again, it’s important to emphasize that most children with ear fluid do not require any monitoring or treatment. Further evaluation and treatment are needed only for children who have had fluid for more than three months, those with hearing loss that causes developmental concerns, or those with recurrent episodes of acute otitis media.

Current treatment options include:

# Nasal sprays (mainly saline-based) – These may provide some relief and are more commonly used in adults.

# Antibiotics – Not recommended. Antibiotics should not be used to treat otitis media with effusion.

# Antihistamines (anti-allergy medications) – Generally not effective, as the condition is not caused by an allergy.

# Steroids (oral or nasal spray) – These may offer short-term relief but have no long-term benefit. Their use is not standard in children.

# Decongestants – Not recommended for children, especially those under two years of age, and there is no evidence they are effective.

# Nasal drops such as Dethamycin – Not effective for long-term use.

# Blowing balloons, salt rooms, and other alternative remedies – These are not effective.

The hardest thing for a doctor is to tell parents that there are no medications or therapies that will significantly change the course of their child’s condition.

The only proven and effective treatment for persistent ear fluid is surgery to insert ventilation tubes.

What are the different considerations before surgery for insertion of ventilation tubes?

Before proceeding with surgery, several important factors should be taken into account:

1. Most children with ear fluid do not require monitoring or treatment. The fluid usually has no short-term or long-term effects and often resolves on its own within a few weeks or months.

2. In many countries, the insertion of ventilation tubes is the most commonly performed ambulatory surgery. At times, it can feel like it’s being done routinely or even commercially. For this reason, it’s important to consult with your pediatrician to evaluate the actual need for surgery. Additionally, seek the opinion of a recommended pediatric ENT specialist, and avoid rushing into surgery without a clear medical indication.

When consulting with the surgeon, be sure to consider various factors that may influence the decision, including:

– The child’s age

– The time of year (there is a difference between scheduling surgery before winter—when viral infections are more common—and before summer—when such infections tend to decrease)

– The number and severity of ear infections the child has experienced

– The time elapsed since the last ear infection

– Whether fluid is present in one ear or both

– How long the fluid has been present

– Most importantly, the degree of hearing loss and any resulting developmental concerns

Making an informed decision, based on a thorough evaluation of all these factors, is key to ensuring the best outcome for your child.

What is surgery for ventilation tube insertion and how is it associated with the third tonsil?

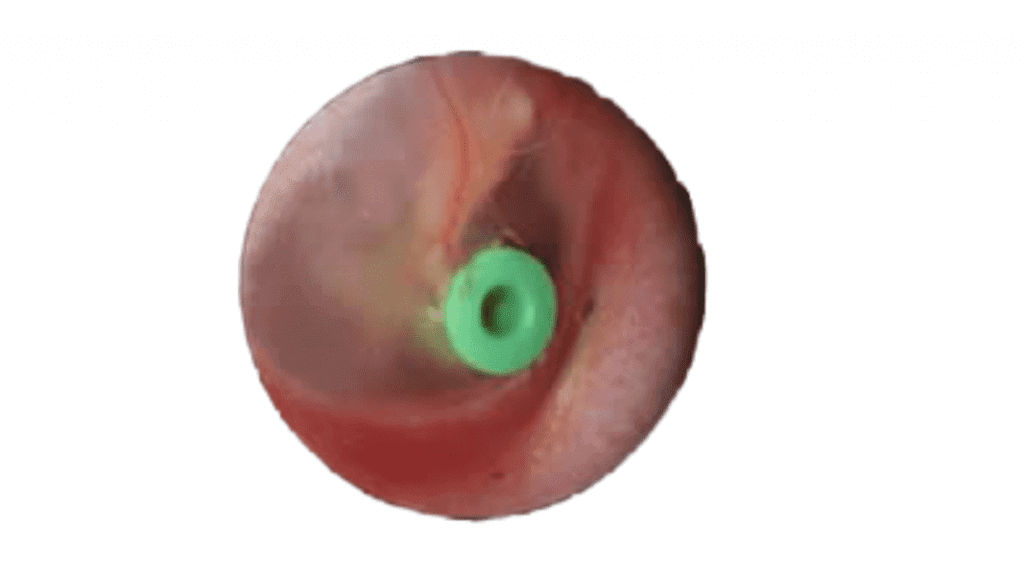

Surgery for ventilation tube insertion involves placing a small tube through a tiny incision made in the eardrum (one in each ear). Once inserted, the tubes allow the middle ear cavity to open to the auditory canal, enabling proper ventilation, drainage of fluid, improvement in hearing loss, and usually a reduction in the frequency of middle ear infections.

There are two types of ventilation tubes:

– **Short-term tubes**, which typically fall out on their own within six months to one year. These are most commonly used in children.

– **Long-term tubes**, which remain in place for a longer period and are used in select cases.

In many cases, surgical removal of the third tonsil (adenoid), which may be causing nasal obstruction, is performed at the same time. For more information on this topic, follow this link.

In summary, ear fluid is one of the most common concerns in pediatrics. If you’ve read and understood the information presented here, you’ll be better equipped to make informed decisions for your child.

Good luck!

For comments and questions, please register