10 rules for childhood winter illnesess

Since the early days of this site, I got feedback from parents, requesting a post on childhood illnesses during the winter. One asked me to write about the common cold, one about cough, and another about when to go see a doctor.

So it’s true that each and every winter is different, and it’s true that no one knows what the next winter will bring upon us (Covid-19? The Flu? RSV?), but still, this is a very basic episode in pediatrics.

I promise that a child whose parents understand what I’m writing about, will get a more appropriate treatment at the next trip to the pediatrician.

So what are “winter-time illnesses”?

Roughly, respiratory illnesses are more common during winter time. It is mostly a combination of runny nose, cough, and dyspnea, with or without fever.

It is a very big and complex subject. So before I’ll try to focus a bit, we must speak the same language. Let’s start with a few definitions. Some are just basic knowledge, but are very important to understand if you want to talk to your physician with the same language.

At the end of this post I will give 10 practical rules. If that is what you will take from this post – that’s more than enough.

Part one: winter illnesses and some definitions

Rhinitis – a typical secretion from the nose. It can be clear and bright, or it can be thick, yellow and green. Parents have the tendency to describe to the doctor the color and texture of the secretions, but is that important? No (Rule #1).

Rhinitis can be caused by numerous reasons, for example – allergy. But, in most cases in children, rhinitis is caused by infections, mainly viral infections.

And another important thing – rhinitis is caused by viruses not air-conditioning. Read more of stuffy nose in children here.

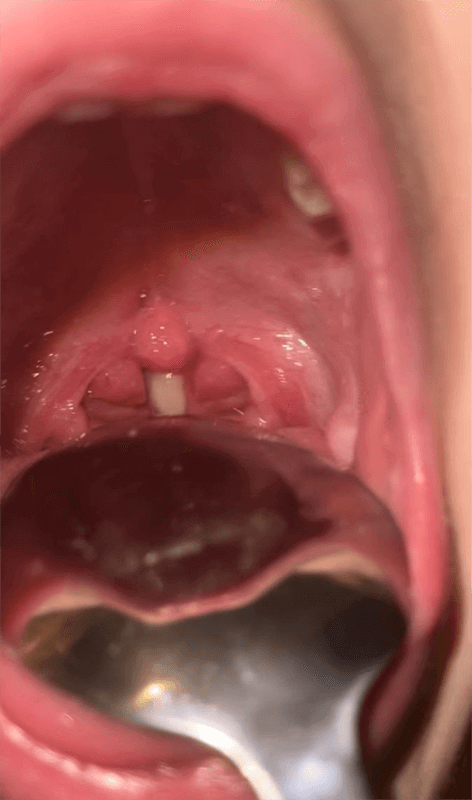

Post nasal drip – this means secretions from the nose (AKA rhinitis, see yhe picture), sliding down the pharynx into the throat and sometimes to the trachea. It is a common reason for illnesses and especially pestering cough in children.

A child with a cold – a child with rhinitis. The color does not really matter.

Upper respiratory tract infection (URTI) – when the upper part of the respiratory system is involved, mainly the nose, sinuses, pharynx, the vocal cord area and the upper part of the trachea. It is in fact an infection not involving the lower part of the respiratory system – the lungs. It is mostly caused by viruses, and is more common at winter time. The signs for such an infection are rhinitis, sore throat, cough, with or without fever.

Lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) – when the lower part of the respiratory system is involved. Symptoms in this kind of illness are similar to URTI, including cough with or without fever. Since sometimes URTI is continuous with LRTI, there can be mixed signs in the clinical presentation.

Many parents come to the clinic and ask – “did the infection went down and reached the lungs?” so where does one infection start (URTI) and the other begins (LRTI)?

The location of the infection is mainly determined after the physician listens to the lungs. If there are abnormal findings when listening to the lungs than it is a LRTI. Does it necessarily means that it is a more serious infection? Absolutely not. read about it ahead.

Part Two: what are the most common childhood illnesses in winter time?

URTI – in fact, a common cold, mostly with a bit of cough. Could be accompanied with fever, or without. Findings in a physical examination will be limited to the upper part of the respiratory tract, and treatment is mainly supportive – lowering the fever and making sure the child drinks enough. You can try using decongestant syrup to relieve a stuffy nose, but mainly in children older than 2 years. The main treatment is still supportive care and a lot of patience.

I’ll repeat this mantra a few times throughout this post – it is very hard for a pediatrician to stand in front of parents who did not sleep at all at night because of the child’s cough and say – “there’s nothing to do, it is a viral infection that will pass on its own” (Rule #2),

This is another reason people leave the doctor’s office with prescriptions to several medications, from Saline inhalations to cough syrup. In addition, when going to the pharmacy, the pharmacist will add herbal syrup (for which he will make more money than on prescription medications). This way parents often feels well treated.

I’m sorry to say, but these illnesses will pass away with or without treatment, with no effect on the duration of the disease whatsoever.

You still want a recommendation? There is no better cure than chicken soup and fresh orange juice! (Rule #3)

Stridor – a more specific and comprehensive post (including audio samples), regarding stridor is already up on the site (link). For the purpose of this post, I will give just a quick taste – stridor is caused by a narrowing in the upper airways. The reasons in children are diverse, from congenital malformations leading to pressure on the trachea, up till’ foreign body aspirations (mostly nuts or little plastic playing parts inhaled by the child).

The most common cause for stridor is viral infection causing inflammation, edema and narrowing of the vocal cords area. It manifests mostly as a young infant going to sleep with a bit of a cold and fever (but not a very high fever) and wakes up in the middle of the night with a typical cough. An example of stridor (barking cough) can be found in the beginning of this chapter. A very stressful situation for the parents.

The treatment is breathing cold, dry air (that is way many parents are opening a window, going to the beach or just driving fast to the ER with the windows down – sometimes the stridor will disappear on the way).

An appropriate medical treatment is steroids – through inhalation, inhaler, syrup or water-dissolving pills.

Bronchiolitis – The small airways are called bronchioles, and an inflammation in this area is called bronchiolitis. It is a common infection, mostly in the first 2 years of life. In fact, all children will suffer from bronchiolitis in the winter time.

Since a few different (viral) pathogens cause the same medical condition (bronchiolitis), you can get this infection several times in the same winter period.

The diagnosis is clinical, after a doctor’s physical examination – he will hear a combination of rales, wheezing and obstruction of lower airways.

Parents will often tell that this disease started as a simple cold, but after a few days (the peak of the disease comes after 4-5 days) there was deterioration in the infant’s condition, including shortness of breath and cough.

This infection can be accompanied with fever, but also without. If there is fever – it can be high. Cough after bronchiolitis can last a few weeks, but the more typical way is for the infant to get better from day to day.

Where did the child get bronchiolitis from?

Usually from the brother and sister who goes to the kindergarten. All of them will be ill simultaneously but the older siblings will manifest in a less severe manner than the younger infant. Sometimes one of the parents will also complain about sore throat or a runny nose.

Why is the presentation so different from one another? Since the parents have encountered this pathogen in the past and have antibodies against it, the toddler in kindergarten also encountered this pathogen a few times, but the youngest sibling gets it the hardest since it is his first time.

For whom bronchiolitis is more dangerous?

Mainly young babies or children with a significant background illness. In several countries around the world, there is a passive vaccine given once a month during the winter periods to populations who are at risk for a significant infection (preterm babies, heart malformations, chronic lung disease etc.). The vaccine is directed mainly against a virus called RSV, which is the main blame for bronchiolitis in children.

What is the treatment for bronchiolitis?

Supportive care.

What do I mean by that? Good hydration for babies who won’t eat or drink, giving oxygen to those needing it (only on hospitals or first care centers) and lowering the fever if there is any. Most children do not need these types of intervention, and those who do – needs to be hospitalized.

There is no other real treatment proven to help bronchiolitis, including cold or warm steam, saline inhalations, bronchodilators or steroids.

Treatment with inhalations or inhalers will be given only to children with recurrent events of wheezing (babies’ asthma) or those who have a significant family history of atopic conditions including asthma, atopic dermatitis, etc.

This reminds me of the second rule – how hard it is for a physician to stand in front of parents and say – it is viral and will pass without treatment.

So, the doctor will say this mantra in the first visit to the clinic, and despite that – in the second visit he will prescribe this treatment or another (inhalation? Inhaler?). Those of you who will come back for the third time could leave the clinic with a prescription for antibiotic – which is totally not necessary. This is because the prevalence of bacterial infection after bronchiolitis is not high (though you could see ear or lung infection from time to time).

What about the flu?

You can find a specific post about the flu vaccine right here.

I just want to say that even in the COVID-19 era, the flu was the most severe viral infection out of all the winter’s viruses in children. High fever for 5 days, headache and muscle pain, sore throat.

The treatment for the flu is mainly supportive, though the prevalence of secondary bacterial infection is a bit higher in children, so you should keep that in mind.

Of course, these are not all the diseases pediatricians see at winter time, there are of course others (sinusitis, laryngitis, otitis media, etc.), but these will get their own, more specific posts.

Part 3: when to go see a doctor?

It does not make any sense for me to tell parents when to go and when not to go see a doctor, without seeing the child. Doesn’t matter if the child is really sick, or quite healthy. That’s because it is mostly a good idea to go see a certified pediatrician and trust his clinical opinion.

For example, a lot of appointments at the pediatric clinic during winter time are because of a runny nose, cough and fever. These are generic symptoms, which can be diagnosed as a simple viral pharyngitis or at the other far end of the spectrum with a diagnosis of bacterial pneumonia.

So can you even chart clear rules about when to worry and when not to worry at all?

Well, I’m gonna try:

Fever – one of the most important symptoms in pediatrics. Most children with a significant illness (for example, a bacterial infection like pneumonia, read more here) will have high fever. On the other hand, most children without a real fever (about 38.0 Celsius) will have a viral infection. This is a very general statement, and there are exceptions to both sides, but let me say this – having a fever above 38.5 is a good reason to go and see a doctor (Rule #4).

An exception are very young babies (up to 60 days old, mainly 30 days and younger), which can present with a low fever even if they have a significant infection (read more here).

Another important term to know is secondary fever. What does it mean? If a child has a febrile illness for 3 days, and the physician determine it is a viral infection, and in the fourth day the fever breaks and the child gets better, and then after 24 hours without fever the thermometer spikes to a higher fever, than this is a secondary fever (within the same illness).

For me, as a clinician, that is a good enough reason to go and see your physician, since a secondary fever can indicate a bacterial complication on top of the early viral infection. So, to conclude: a child with a secondary fever within the same illness, needs to be evaluated by a physician (Rule #5)

The age of the child – The younger the child is – the higher the chances he will have a bacterial infection. This means that with a baby who is younger than 2 months, you should go see your pediatrician about the littlest of things, even if it is just a cough (Rule #6). The threshold for seeing a physician can of course be a little higher with a coughing 16 years old that continue to play soccer with his friends daily. I hope you understand the general idea.

Duration of symptoms – A child with a 39.0 fever and cough for about an hour is not the same as the same child with the same symptoms but for a 4 days’ duration. In the first case, it will probably be a viral infection. In the second case, it will also probably be a viral infection, but that’s a statement that needs to be made by a pediatrician after examining the child (since the risk for a bacterial infection here, is higher).

How the child feels and looks when the fever breaks – Children with high fever can look bad, tiered, pale, in pain and with shortness of breath. But a very important factor is how the child looks when the fever breaks. If he is happy and vital, without respiratory distress, or in other words – looks like his healthy self, than I am less concerned. This doesn’t eliminate the need for a medical evaluation, but the case is not as worrisome as a pale child that moans and having trouble breathing. These are children who need a prompt medical evaluation.

So, Rule #7, take a close look at how a child looks when the fever breaks. If he still looks ill, pale, or moans, go see a physician promptly.

The characteristics and intensity of symptoms – In the days when I worked at the public clinic, I would arrive to the clinic 5 minutes before my shift started and just after opening the computer, a mother to a 2 years old child would be siting across the table saying that the kindergarten teacher said the child had a cough.

From a pediatrician point of view, it is quite different examining a child who was healthy enough to go to kindergarten in the morning with a cough noticed only by his teacher, than examining a child who coughs every night for 3 weeks.

The first child will probably have nothing. The latter – maybe has something. This is the time to remind, that a healthy child will cough up to 13 times a day (Rule #8). So if it is the only complaint, there is really no need to go to your pediatrician.

Background illnesses – Differentiate a healthy child, from one with a chronic condition, including immunodeficiency, cardiac or pulmonary malformation or even asthma.

There is no need to turn every child with a history of inhalations once or twice, or a preterm born on 36 weeks of gestation into a chronic patient.

Most children with chronic illnesses tend to present with complications even with the simplest infections, and needs to be evaluated early by their physician (Rule #9).

Since I can’t leave this list with just 9 rules, I will try to say a few things from the heart, so we can make that rule #10.

Being a pediatrician at wintertime is a difficult task. It is especially difficult when you have 5 minutes per patient, and pretty much everybody has the same symptoms. The job of a pediatrician in the winter is to find the needle in the hay stack. Who is the one child (and there are few of those) who really needs the correct antibiotics? Who needs a chest X-ray? Who needs inhalation?

So, rule #10 is to find a good pediatrician, which is an expert in his field but also pleasant and with good availability.

Bring him a lovely chocolate box in the beginning of winter, and trust his judgment and opinions. Prepare for the visit at the clinic, and tell about the child’s symptoms in a chronological and objective manner without sayings like “the teacher said” of fairy tales about the color of the child mucus.

Let’s get through this winter safe and well!

10 basic rules for getting through the winter time with a toddler:

1- Does the color of the mucus matters? Practically no.

2- There is nothing harder for a pediatrician to stand in front of stressed parents and say – “there is nothing to do, it is a viral infection that will pass with or without specific treatment”. So, a lot of children are getting unnecessary treatments.

3- The best treatment for the common cold (for children and adults) is chicken soup and fresh squeezed orange juice.

4- If a child has at least two separate fever spikes over 38.5, go see your pediatrician for a checkup.

5- A child with a secondary fever within the same illness needs to be evaluated promptly.

6- Babies up to 2 months old, with recurrent cough, fever or respiratory distress needs to be medically evaluated.

7- Notice how your child feels and looks when the fever breaks. If he does not look well, if he is pale, moans or experiencing shortness of breath – go and see your pediatrician.

8- A healthy child coughs up to 13 times a day.

9- Children with chronic conditions tend to get complicated even in the simplest infections, and needs to be evaluated early.

10- Get a good, pleasant and professional pediatrician, and trust his judgment.

In summary:

For comments and questions, please register